Assessing the risks for implementing controlled human infection trials

| 9 August, 2019 | Developers f1000 |

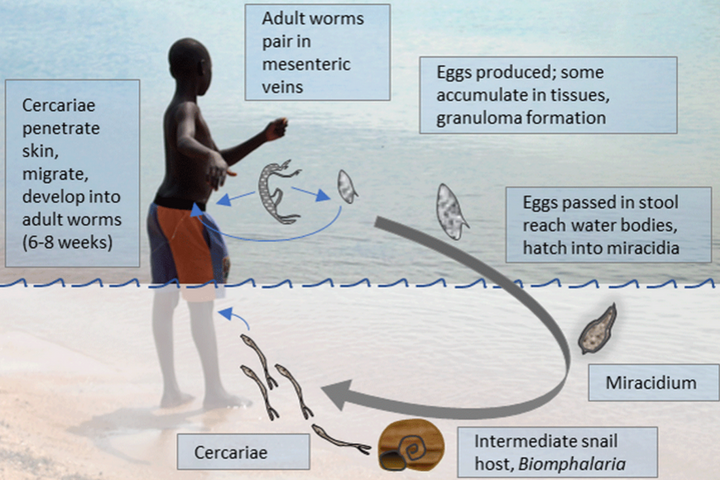

Schistosomiasis is a disease caused by parasitic worms and is affecting approximately 230 million people worldwide. There is currently no vaccine available but controlled human infection models are considered a valuable approach to develop a much-needed vaccine.

Researchers are working on establishing such a model in Uganda where schistosomiasis is highly endemic. A member of that group is Jan Pieter Koopman, Leiden University Medical Center, who summarises the risks associated with carrying out a controlled human infection model for schistosomiasis and the precautions that need to be considered.

Assessing the risks

The past few years we have been working towards establishing a controlled human infection model with Schistosoma mansoni (CHI-S) study in Uganda. In 2017, a stakeholder’s meeting was held to discuss the scientific and ethical issues related to such a study.

This meeting resulted in a roadmap to implement the CHI-S model. One of the steps proposed included conducting a risk assessment, the aim of which was to identify potential risks associated with a CHI-S in Uganda and to describe measures to mitigate these risks.

Precautionary steps

There are several risks to consider at different stages of the trial. In our risk assessment, we listed three options describing the use of local or imported snails and a local or Puerto Rican schistosome strain for the CHI-S.

Precautionary measures should be in place when non-endemic snails are used to prevent the accidental escape of a snail into the environment. Similarly, if the Puerto Rican strain is used for infection, strategies will need to be developed to avoid natural infection at the same time as the CHI-S.

Concurrent natural infection could result in hybridisation of the Puerto Rican strain with local strains: it is difficult to know what the characteristics of such hybrids might be (although, reassuringly, the strain is sensitive to praziquantel, the drug used to treat schistosomiasis in Uganda).

We use single sex infection in our model, only using males, to avoid participants getting diseases related to egg disposition. A mixed infection due to natural exposure during the trial period could have harmful effects for the participants. This is another reason for avoiding concurrent natural infection. We identified several strategies to reduce the risk of a natural infection by e.g. avoiding bodies of waters, such as ponds and lakes; full clearance of pre-existing infection before the CHI-S trial starts; and abrogation of the infection as soon as the trial endpoint has been met.

Lastly, risks related to the infection itself should be considered. These risks not only include symptoms caused by the infection or symptoms related to the treatment with praziquantel, but also include the risk of misunderstanding controlled human infection studies. Because participants are purposefully exposed to an infectious agent, careful explanation is needed to avoid misunderstandings or rumours.

Ecological hazards

The main concern of importing non-native laboratory vector snails, from the Netherlands to Uganda is the ecological hazard that may follow when a snail accidentally escapes and establishes a colony outside the laboratory. It is difficult to predict what the exact consequences would be, but the Biomphalaria glabrata could potentially spread rapidly due to the lack of a natural enemy.

We proposed several control measures to reduce the probability of this occurring. These consist of precautionary measures for the snail housing facilities, such as physical barriers and restricted access, and the development of a containment strategy. Although the Biomphalaria glabrata snail is not endemic to Uganda, it has previously been held at the Vector Control Division of the Ministry of Health for a different project.

Safe implementation

Our preferred choice to safely implement CHI-S trails is to use the Puerto Rican schistosome strain and a local snail species. We decided not to import snails from The Netherlands. Although control measures reduce the risk of Biomphalaria glabrata establishing a colony outside the laboratory, the added risk would be unnecessary, because local snails are also susceptible to Schistosoma mansoni infection.

We also believe that using the Puerto Rican strain would be the safest way forward, because we’ve established its susceptibility to praziquantel. Control measures will be in place to avoid the spread of this particular strain into the environment either as a result of a mixed infection in the trial participants or via contaminated materials.

Although we currently propose the use of the Puerto Rican strain, we are also considering developing a Ugandan schistosome lab strain.

Community involvement

This would be the first CHI study to be conducted in Uganda, so we need to carefully explain the process to the community and that it involves deliberately exposing participants to an infectious agent leading to symptoms of the infection. Rumours or misunderstandings can greatly affect the conduct of the study and that of other health research and services.

We believe it is therefore important to provide information about the study in an understandable manner to community leaders and participants. Community leaders can be instrumental in identifying misinformation and in helping address this.