Transforming cooking in households to improve air quality

| 23 March, 2020 | Developers f1000 |

Kanyiva Muindi, is a FLAIR Research Fellow and an Associate Research Scientist at the African Population and Health Research Center (APHRC) in Kenya. She won her Future Leaders – African Independent Research (FLAIR) Fellowship through her drive to make a difference to the lives of women in her county and eventually across the African continent. In this blog, she tells us about her FLAIR Fellowship work, where she rolled out an ethanol cookstove intervention in a rural community in Kenya to reduce household air pollution.

FLAIR Fellowships are offered to talented African early career researchers who have the potential to become leaders in their field. These fellowships provide the opportunity to build an independent research career in an African institution and to undertake cutting-edge scientific research that addresses global challenges facing developing countries. The Fellowship is a partnership between the African Academy of Sciences (AAS) and the Royal Society, supported by the Global Challenges Research Fund (GCRF).

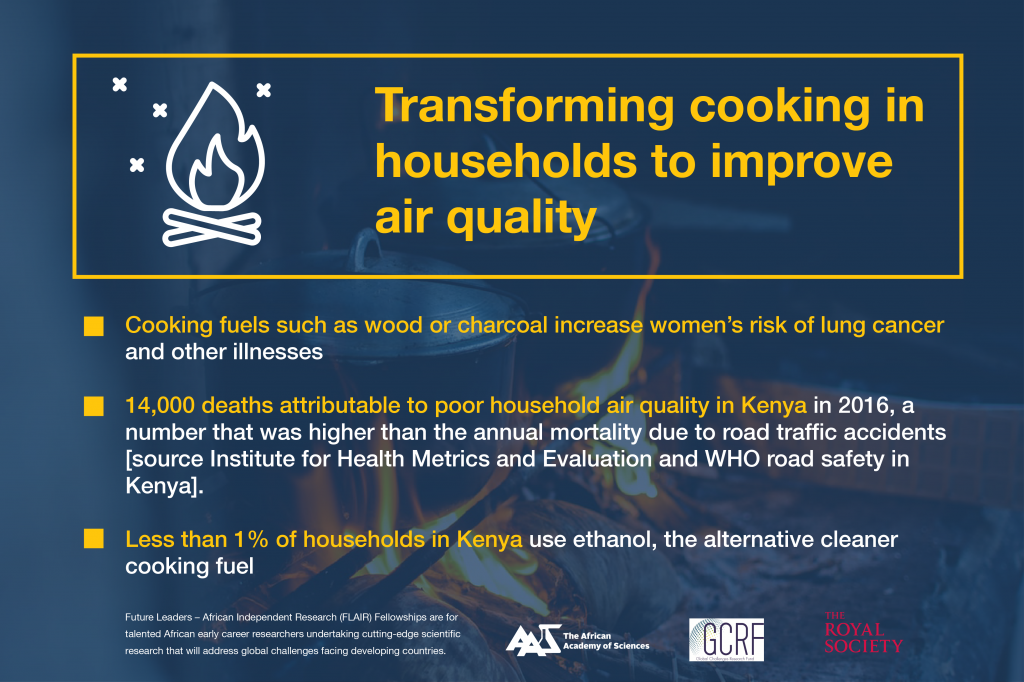

Cooking should be a safe and healthy skill, but it is costing the health, and even the lives, of women in Kenya and Africa. Cooking fuels, such as wood or charcoal, can contribute to household air pollution increasing women’s risk of lung cancer and chronic-obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) compared with women who use cleaner fuels to cook. In 2016, estimates for Kenya indicate that 14,000 deaths were attributable to poor household air quality, a number that is higher than the annual mortality due to road traffic accidents [source Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation and WHO road safety in Kenya].

Winning a FLAIR grant to improve air quality

My journey was motivated by personal experiences cooking using firewood over a three stones stove as a young girl, as well as through my observations during field work in the slums of Nairobi. It was here that it became apparent that the burden of nourishing the family lies heavily on women, and in times of financial distress when resources are limited, women had to find alternative fuels to cook for their families. These included plastics, cloth rags, as well as foam (the kind used in making mattresses), which all have serious implications for air quality in the home and for personal exposure and consequently their health.

As a recent public health graduate and a fresh post-doctoral fellow at the African Population and Health research Center, I needed to find funding to allow me to focus on my research on air pollution. When I saw the call for applications for the FLAIR fellowship, I did not hesitate, despite having little time to develop the proposal and budget.

I felt confident that I would get the funding given the difference I wanted to make for mothers living in Kenya, who are tasked with cooking for the family. I believe my application was successful as it addresses a common challenge in many countries of the world, household air pollution arising from the use of fuels, such as wood and charcoal.

Given that every human must eat to survive, cooking has become an integral part of our culture. However, the fuels we use to cook and the stoves in which the fuels are burnt, can contribute to air pollution. The majority of households in Africa are dependent on wood or charcoal for their cooking, and the cultural roles that assign household chores, including cooking, to women and girls and children under their care, means that our mothers and daughters continue to breathe harmful air and many lose their lives while working towards sustaining their families.

I set out to provide an alternative cleaner burning and affordable fuel, ethanol, to rural households to reduce the burden of household air pollution. This has the potential to transform the cooking practices, and livelihoods, across the continent, and the associated health benefits of clean cooking options.

Setting up a research team

The FLAIR fellowship, my second Post-doctoral fellowship, is giving me the opportunity to grow a team and possibly establish an environmental health research unit within my host institution, which will expand the networks we have and span in focus beyond air pollution. Given the numerous environmental challenges that we face as a country and across Africa, the possibilities of impact for this unit will be immense.

My first year on the fellowship was faced with a number of challenges that made it difficult to implement my work. The biggest challenge was procuring the equipment needed to monitor air quality. The process took longer than anticipated and given the proposed study design, my only option was to wait until all pieces of the equipment were delivered. I would advise applicants planning to import any piece of equipment or reagents to make sure that they generously allocate time in their work plan to avoid delays. I would recommend allowing for implementation (if the study design allows) as they wait for equipment to avoid delays in carrying out the project.

I believe post-doctoral training is important in Africa as governments are now awakening to the realization that their decisions need to be evidence driven. Post-doctoral training arms fellows with requisite research skills, as well as management skills, that they need to run projects aimed at providing evidence for informed policy and action. These skills can then be passed on to upcoming researchers who the fellows mentor through teaching and/or supervision. One of the aspects of the fellowship that is impacting my career is the formal mentorship that is part of the journey. This is providing important support and growth in my field and is opening doors to future collaborations with teams across the globe.

I wish to see more funding coming from African governments, industry and philanthropies to support this program that is crucial in developing early career scientists given the many challenges that the continent faces. This funding will complement the available external funding to either increase the number of African scientists working towards solving some of the continent’s pressing challenges or increase the value of the fellowship which may facilitate longer term research. It can also enable setting up of a research team with protected time to focus on the proposed work.

The future of ethanol in households

I hope my research will reveal what works and what does not work in the introduction of ethanol cookstoves in households. This will inform the best approaches to use when scaling up ethanol stoves in rural communities, not only in Kenya but throughout Africa. Although less than 1% of Kenyan households use ethanol as a cooking fuel, it remains a promising fuel that can easily be produced in communities across the country and indeed across the continent to ensure households transition to clean cooking.

Transitioning to ethanol would also help in the fight against climate change through reduced carbon emissions associated with charcoal and wood use, while also encouraging the reforestation of areas where indigenous forests have been decimated to meet the demand for these fuels.

Some of the feedback from some preliminary community meetings has been encouraging as there is excitement from women and men alike, at the introduction of ethanol cookstoves that will provide cleaner and faster cooking compared to wood or charcoal. Our future meetings shall be focusing on educating the community on safe use of ethanol fuel, as well as entrepreneurial training for women and youth groups for potential engagement in the value chain.